|

Listen to this Article

|

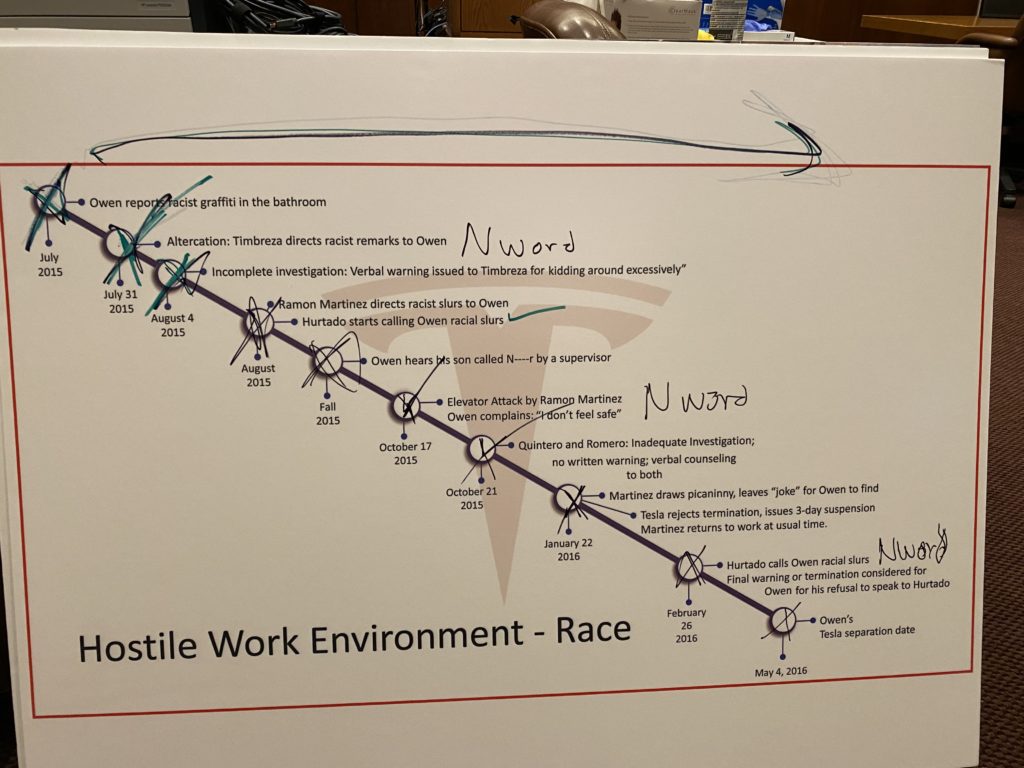

On October 4, 2021, a Northern California federal jury unanimously found Tesla, Inc. liable for severe and pervasive racial harassment for near daily use of the N-word directed at our client, Owen Diaz. The Jury awarded Mr. Diaz $136.9 million in damages. This verdict of $136.9 million is believed to be the largest jury verdict for a single plaintiff race harassment case in American history. CCRLG’s team included Partners Larry Organ and Navruz Avloni, Associate Cimone Nunley, Paralegal Sabrina Grislis, and Trial Specialist Susan Organ. Here are the facts behind the largest jury verdict for racial harassment in the history of the United States.

On June 3, 2015, Owen Diaz came to Tesla’s Fremont, California car factory with high hopes of helping address climate change by building cutting edge cars in a 21st Century factory. But after he started working there, he found that the factory was more from the Jim Crow Era.

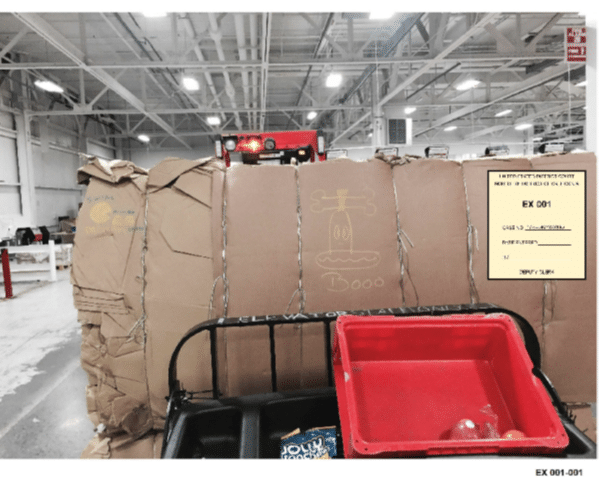

Mr. Diaz was called the N-word over sixty times by supervisors and he was told to “go back to Africa.” One supervisor left a picaninny drawing on recycled cardboard near the elevators where Mr. Diaz would find it. Mr. Diaz saw racist graffiti in multiple bathrooms throughout Tesla’s Fremont factory. Mr. Diaz also witnessed his son being called the N-word by his son’s supervisor. Mr. Diaz first complained about the N-word to his lead just under 2 months after starting at Tesla. Several employees corroborated the racist conduct. No remedial action was taken to ensure that other employees did not engage in similar conduct. In fact, one of Mr. Diaz’s supervisors claimed that the use of the N-word was not corroborated in an email even though at trial he admitted it was. In addition to Mr. Diaz, three other employees, including supervisors, heard the N-word on a daily basis as they walked around the factory. They did not take remedial action.

Sensitive Content

Click on the button below to see the image containing the senstivie content.

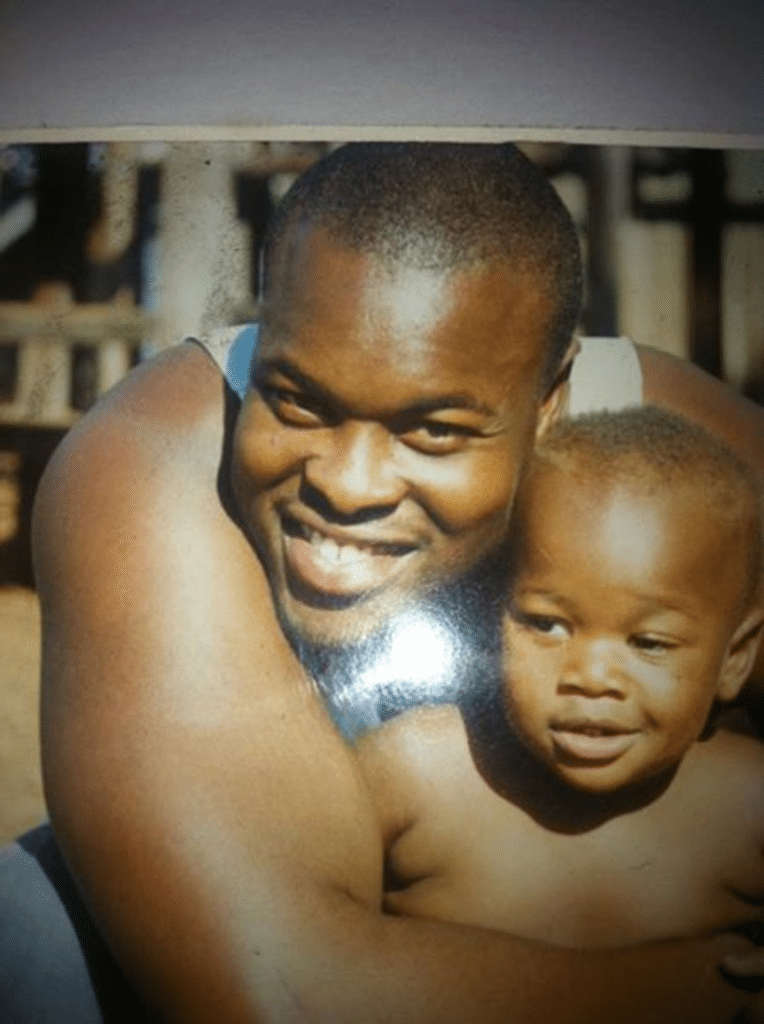

Owen Diaz is a 53-year-old Black man. Before he began working at Tesla, Mr. Diaz was known to be confident and proud. His daughter described him as a “typical dad” who “was always joking.” He was not someone who cried. Expert psychologist Dr. Reading testified that before working at Tesla, Mr. Diaz had no psychological issues or difficulties.

Mr. Diaz was subjected to egregious verbal abuse beginning on his second day, when co-worker Judy Timbreza started calling him “n****r” and “porch monkey,” first in Spanish, and then when he complained, in English too. Eight to ten other co-workers also started calling Mr. Diaz “n****r,” and direct supervisors Martinez and Hurtado called him “n****r” over 60 times.

The word “n****r” is not a mere “offensive utterance.” The Ninth Circuit has stated that “n****r” is “perhaps the most offensive and inflammatory racial slur in English, … a word expressive of racial hatred and bigotry.” Swinton v. Potomac Corp., 270 F.3d 794, 817 (9th Cir. 2001) (quoting Merriam–Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 784 (10th ed. 1993)), see also Monteiro v. Tempe Union H.S. Dist., 158 F.3d 1022, 1034 (9th Cir. 1998) (describing “n****r” as “the most noxious racial epithet in the contemporary American lexicon.”). The word “sums up … all the bitter years of insult and struggle in America, [is] pure anathema to African-Americans, and [is] probably the most offensive word in English.” Ayissi-Etoh v. Fannie Mae, 712 F.3d 572, 580 (D.C. Cir. 2013) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring) (cleaned up). Dr. Reading observed that slurs like “n****r” are particularly damaging in the workplace given the amount of time employees must spend at work, the economic forces that require employees to remain under abusive work conditions, and the workers’ reliance on their employers for protection from harassment.

The racist conduct of Tesla’s supervisors was not limited to that epithet. Hurtado called Mr. Diaz “boy,” while Martinez told him to “Go back to Africa” and left Mr. Diaz a racist caricature in the workplace. Mr. Diaz also continuously experienced racist graffiti in the bathroom, including “n****r” and phrases like “Death to all [n****rs].” Nor was the abuse purely verbal: as the jury heard, Martinez joined racist epithets with physical threats, leading Mr. Diaz to fear for his safety. The harassment made Mr. Diaz’s job harder and his life more bleak.

Sensitive Content

Click on the button below to see the image containing the senstivie content.

At trial, Tesla sought to rewrite reality, asking the jury to believe that the racial harassment of Owen Diaz “was never condoned by Tesla” and that Tesla took appropriate “disciplinary action in response to all of the incidents” of which it was aware. The truth—that Tesla willfully and maliciously ignored the extensive evidence of pervasive harassment of Mr. Diaz—is likely one of the reasons the jury imposed substantial punitive damages. The jury saw Tesla’s Anti-Handbook Handbook with its joking reference to racist harassment as “stupid stuff.” It heard many witnesses testify that Tesla repeatedly ignored complaints of harassment. It knew that Tesla issued minimal discipline, if any, to serial harassers—even after a physical assault. It also knew that Tesla supervisors falsely denied having received complaints, quashed investigations without making even token efforts to question witnesses or review security video, and were impeached by their own emails.

Mr. Diaz was thrilled to have the opportunity to work for Tesla, beginning in June 2015. He thought it would be a great job and was excited to join a team of workers dedicated “to mak[ing] the earth a little bit better for the next generation.” But the reality was as ugly as could be. As Mr. Diaz quickly learned, Tesla’s Fremont factory was a hotbed of unrelenting racial hostility, which Tesla condoned at its highest levels. Only two days into the job, Mr. Diaz saw the racial slur “n****r” scrawled throughout the bathroom stalls. Those detestable epithets remained throughout his employment, as did equally demeaning graffiti such as swastikas and statements like “Death to all [n****rs].” Mr. Diaz complained about this graffiti on multiple occasions. But Tesla did nothing about it, as Mr. Diaz was reminded every time he needed to relieve himself. Tesla now asks the Court to disbelieve this evidence, claiming it had a strict policy of requiring HR staff to photograph and report all offensive graffiti. There is no evidence in the record of that supposed policy or its enforcement.

Within about a month after Mr. Diaz started, for a period of at least several weeks, Mr. Diaz’s co-worker Judy Timbreza repeatedly assailed Mr. Diaz in Spanish with such epithets as “porch monkey” (in Spanish) and “n****r” (in Spanish and English), making Mr. Diaz feel “less than human.” Diaz complained to supervisor Tom Kawasaki, who spoke to witnesses who confirmed Timbreza’s use of these slurs. Tesla then put Ed Romero, a higher-level supervisor, in charge of the investigation.

At trial, Romero initially insisted he had personally investigated but was unable to find a corroborating witness. On cross, Romero acknowledged having previously admitted not conducting an investigation. His own emails confirmed that “Mr. Owen [sic] says this has happened before.” Romero rejected Mr. Diaz’s complaint on the false basis that it was uncorroborated, even though he later admitted that Kawasaki had confirmed Timbreza’s racist slurs. While Romero claims to have given Timbreza a warning (which the jury never saw) for “kidding around,” such a warning would have dramatically understated the severity of Timbreza’s abuse and sent a clear message that such conduct was condoned, not condemned.

Mr. Diaz’s co-workers joined in the racial abuse, with 8-10 of them repeatedly calling Mr. Diaz “n****r,” again without intervention from Tesla management. It was not just co-workers. Beginning in August 2015, Tesla supervisor Robert Hurtado started calling Mr. Diaz “n****r” and “boy,” not once, not twice, but more than 30 times, sometimes coupled with demeaning race-based comments, like “You n****rs are lazy.” Supervisor Ramon Martinez called Mr. Diaz “n****r” to his face more than 30 times. Five witnesses corroborated Mr. Diaz’s testimony about widespread use of “n****r” at Tesla. Wheeler, Jackson, and Kawasaki testified that they heard “n****r” almost every day. Martinez admitted that “n****r” was still being used up to the date of trial. Kawasaki confirmed that Martinez regularly used the Spanish words “mayate” and “chongo.” One day, when Mr. Diaz was bringing lunch to his son Demetric—who worked in a different part of the factory (where Mr. Diaz thought his son would be safe from abuse—Mr. Diaz witnessed Demetric’s white supervisor yelling at him, “I can’t stand all you [fucking] [n****rs].” Demetric later complained, but Tesla did nothing. Mr. Diaz testified that this gutting event “broke me and I think my son.” According to Demetric, “that’s the first time I seen my father, like, really feel like he couldn’t do anything for me. Like, he didn’t know what to do.” Dr. Reading testified that Mr. Diaz’s inability to protect his son from such racist abuse led to a permanent break in their relationship.

Tesla asked the jury to ignore the evidence, insisting it was only aware of three complaints of harassment from Mr. Diaz (which is three too many). Yet the record shows Mr. Diaz complained to Romero about the restroom graffiti and use of racial slurs on many occasions (and complained as many as seven times about Hurtado, Martinez, and co-workers calling him “n****r”). No one in a position of responsibility at Tesla took corrective action, which heightened Mr. Diaz’s sense of helplessness while emboldening his harassers. Romero insisted he did not know of any complaints of racial taunting—until the jury learned that Romero had emailed Tesla’s liaison at nextSource (Wayne Jackson) in December 2015, copying Tesla’s HR Department and its custodial program manager, Victor Quintero, acknowledging that Romero had received complaints about use of the word “n****r” in the area near the elevators (where Mr. Diaz was stationed).

Mr. Diaz found his supervisors’ racial abuse dehumanizing, describing Hurtado’s reference to Mr. Diaz as “boy”—“a term that slave masters used to use against black people to let them know that they were [the slaveowners’] property”—even though “I’m a grown man.” Dr. Reading testified that use of racial slurs in the workplace creates a high risk of psychiatric injury, because they can erase a victim’s identity and carry “connotations of violence historically and also in the present context.” The supervisors’ use of slurs heightened these negative impacts and deepened Mr. Diaz’s “sense of hopelessness.” Mr. Diaz could not stop the harassment because his Tesla supervisors were among the worst offenders.

In October 2015, Ramon Martinez’s harassment of Mr. Diaz turned physical. After Martinez overheard the end of a work-related conversation between Mr. Diaz and new hire Rothaj Foster, Martinez aggressively rushed toward Mr. Diaz, cornering him inside the elevator, screaming racial slurs and yelling “[n****rs] aren’t shit,” and bringing his balled-up fists within inches of Mr. Diaz’s face. Backed up against a wall, Mr. Diaz was forced to climb over a piece of equipment to avoid being hit. Martinez did not back down until Mr. Diaz pointed to the elevator’s surveillance camera system recording their encounter. Mr. Diaz promptly complained that Martinez had violently assaulted him, telling supervisor Romero, “I don’t feel safe around [Martinez] now… I don’t need any problems. I just want to do my job,” and identifying Rothaj Foster as a witness. Martinez pre-emptively complained that Mr. Diaz had acted unprofessionally—ironically, one of the few complaints that Tesla actually investigated. For four days, Tesla ignored Mr. Diaz’s complaint (in distinct contrast to its quick response to Martinez’s complaint against Mr. Diaz), until a member of the HR Department acknowledged Mr. Diaz’s complaint only to conclude that “we do not need to do any formal investigation” because it was a “he-said, she-said” situation. No one interviewed eyewitness Rothaj Foster or reviewed the surveillance video. Despite Martinez’s clear violation of Tesla’s purported workplace safety and anti-discrimination policies, Romero issued a mere verbal warning for inadequate professionalism to Martinez and Mr. Diaz.

Martinez was not done harassing Mr. Diaz. In January 2016, Martinez drew a racist effigy and left it for Mr. Diaz in front of the elevator doors. Mr. Diaz immediately recognized the cartoon and its racist message. His “stomach dropped” as though someone had kicked him. Martinez acknowledged that his effigy was a rendition of “Inki the Caveman,” a midcentury racist caricature that Warner Brothers pulled from television in the 1950s as too racist, in which the principal character chased “after fried chicken and was a buffoon running around saying ‘mammy’ and ‘master.’”

Mr. Diaz again complained, in writing. Recognizing the seriousness of this offense, nextSource manager Wayne Jackson recommended that Martinez be fired. Tesla manager Victor Quintero rejected that recommendation and decided to issue just a written warning, although he eventually imposed a three-day suspension after Jackson insisted on more serious discipline. Soon, Martinez was back on the job; but again, there is no evidence any warning was actually given. Moreover, Quintero decided against more severe discipline without even waiting for results of an investigation. The discipline was determined on January 22nd, yet the investigation was completed only on January 25th. Martinez claimed to have apologized to Mr. Diaz, but what he said was, “You people [i.e. Black people] can’t take a joke.”

In February 2016, Mr. Diaz was near the breaking point. When supervisor Hurtado resumed his racist invectives, Mr. Diaz complained to Tesla manager Joyce DeLaGrande. This time, Mr. Diaz’s complaint was not only ignored, but it completely backfired. DeLaGrande listened to Mr. Diaz’s detailed narrative of racial abuse but decided not to investigate. Instead, she asked Romero to fire Mr. Diaz for being “unprofessional”—an outrageous response to an employee’s efforts to protect his dignity and emotional health by complaining about racial harassment. Shortly thereafter, Mr. Diaz requested bereavement leave and then realized he could not bring himself to return to the harassing atmosphere at Tesla.

This case should encourage companies to prioritize creating a better workplace for everyone who performs work for them – contractors, as well as employees. In addition to enforcing their existing policies, companies have a responsibility to properly train their workforces. Communicating expectations regarding how people should behave in the workplace environment is a fundamental duty incumbent on all companies.

Owen Diaz brought a race harassment case against Tesla, Inc. under the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (also known as Section 1981) because he was forced to endure widespread use of the N-word and other racist conduct. Section 1981 was passed by the Reconstruction Era Republican Congress to address slave owner’s persistent efforts to continue to indenture their former slaves. Section 1981 provides broad remedies for people who have been subjected to racial harassment and discrimination.

The case was filed against Tesla, Inc., and was eventually assigned to Judge William Orrick.

A jury has found that from 2015 to 2016, Mr. Diaz was subjected to severe and pervasive racial harassment.

One juror noted that Tesla “claims to have a zero tolerance policy, but suspended rather than fired, and ignored rather than rectified or retrained their employees on proper prevention,” said the juror, who asked not to be identified. Eight jurors delivered the verdict Monday about four hours after the trial ended.

A member of a jury that awarded former Tesla worker Owen Diaz a $137 million said Tuesday that Tesla uses contract employees as a way to mitigate their own responsibility for the culture within their factories.

The company does that to avoid “taking responsibility for the events and people within their factories,” said the juror, who asked not to be identified. “With the punitive damages we want Tesla to take the most basic preventative measures and precautions they neglected to take as a large corporation to protect any employee within their factory.”

After the jury returned the verdict in favor of Plaintiff, Tesla filed a post-trial brief challenging the jury’s decision. In response, Mr. Diaz made a statement, that “[u]nless the court holds Tesla fully accountable for its conduct, including by accepting the jury’s deterrent punitive damages award, Tesla will continue to engage in the same reprehensible conduct,” and that “Tesla’s post-trial briefing shows that it has still not learned its

lesson.” The parties are still awaiting the Court’s ruling on Tesla’s post-trial brief.

Mr. Diaz’s legal team includes the California Civil Rights Law Group’s Larry Organ, Navruz Avloni, Cimone Nunley, Susan Organ and Sabrina Grislis, as well as J. Bernard Alexander of Alexander Morrison & Fehr.